Understanding iodine deficiency

Iodine is a crucial mineral needed for thyroid hormone production; consequently, a deficiency can lead to serious health issues, including hypothyroidism. Approximately 2 billion people suffer from iodine deficiency (ID). Moreover, some 50 million people present with clinical signs, making it the leading cause of preventable brain damage. Research shows that an excess of iodine, as well as a deficiency, can instigate hypothyroidism.

Symptoms of iodine deficiency

Common symptoms include:

– Fatigue and weakness

– Weight gain

– Depression

– Cold intolerance

– Cognitive impairment (brain fog, forgetfulness)

– Dry skin and hair loss

– Goitre (enlarged thyroid gland)

The connection between iodine and hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is an endocrine disorder characterised by insufficient thyroid hormone production. The most common causes include iodine deficiency and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. In iodine-deficient areas, hypothyroidism is primarily due to low iodine intake. In iodine-replete areas, autoimmune thyroid disease is more prevalent.

How iodine deficiency affects thyroid function

The thyroid gland regulates growth, development and metabolism. It needs iodine to produce the thyroid hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) is produced by the pituitary gland. When T3 and T4 levels are low TSH signals the thyroid to produce more T3 and T4. If iodine levels are deficient, the thyroid gland becomes overstimulated and enlarged in an attempt to capture more iodine. The thyroid gland can compensate for mild to moderate deficiency, however, prolonged iodine deficiency can cause goitre, impair metabolism and lead to hypothyroidism.

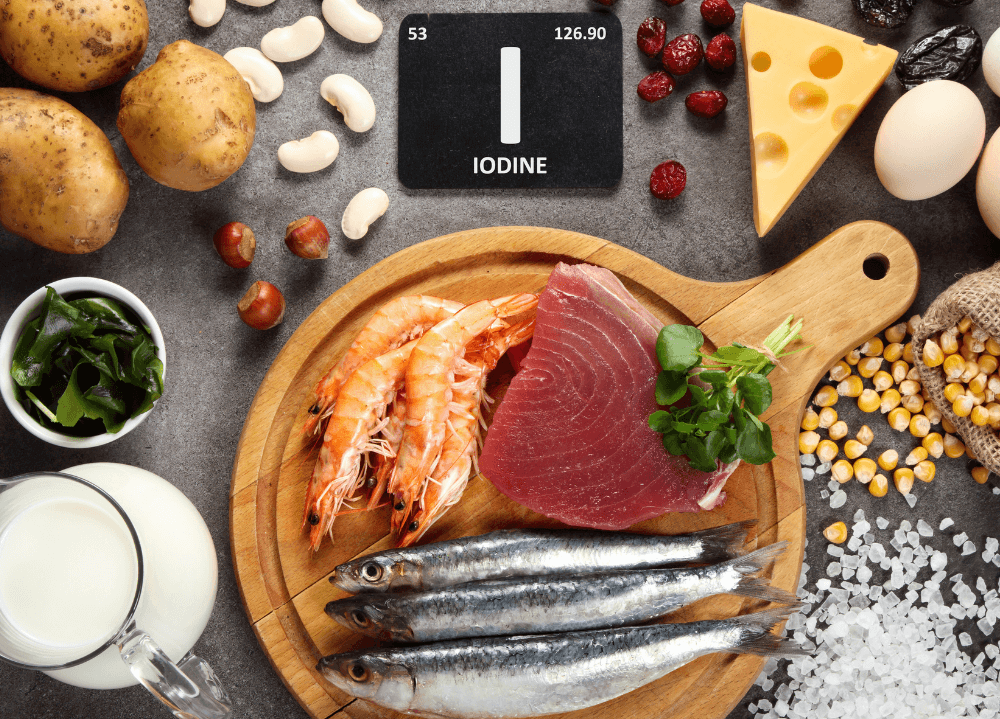

Sources of iodine in the diet

Iodine is naturally found in:

– Seaweed and seafood (highest iodine levels)

– Fortified bread and iodised salt

– Dairy products like milk and cheese

– Eggs and some fruits/vegetables, depending on soil iodine levels

Table 1. Approximate iodine content of various foods

Food | Micrograms of iodine per 100g | Micrograms of iodine per serve | Serving size |

Oysters | 160 | 144 | 6 oysters - 90g |

Sushi (containing seaweed) | 92 | 92 | 1 sushi roll - 100g |

Canned salmon | 60 | 63 | 1 small tin - 105g |

Bread (except organic bread) | 46 | 28 | 2 slices bread - 60g |

Steamed snapper | 40 | 50 | 1 fillet - 125g |

Cheddar cheese | 23 | 4 | 2.5cm cube - 16g |

Eggs | 22 | 19 | 2 eggs - 88g |

Ice cream | 21 | 10 | 2 scoops - 48g |

Chocolate milk | 20 | 60 | 1 large glass - 300ml |

Flavoured yoghurt | 16 | 32 | 1 tub - 200g |

Regular milk | 23 | 57 | 1 large glass - 250ml |

Canned tuna | 10 | 10 | 1 small tin - 95g |

Bread (organic) | 3 | 2 | 2 slices - 60g |

Beef, pork, lamb | <1.5 | <1.5 | 2 lamb loin chops |

Apples, oranges, grapes, bananas | <0.5 | <0.6 | 1 apple |

Iodine fortification programs

Many countries have implemented iodine fortification programs to combat iodine deficiency. With this in mind, the most common approach is iodised salt, but some nations also fortify bread and milk.

In Australia, mandatory bread fortification with iodised salt began in 2009. Research shows that eating three slices of fortified bread daily can significantly improve iodine levels. Even with iodine fortification, iodine deficiency remains a problem in some countries, including Australia. Australian soil is naturally low in iodine, leading to lower levels in many locally grown foods.

Table 2. Iodine deficiency table

Deficiency levels Iodine levels micrograms Normal >100 Mild 50-99 Moderate 20-50 Severe <20

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Goitrogens: substances that block iodine absorption

Disrupting thyroid hormone production, goitrogens are compounds that interfere with iodine absorption and thyroid function, leading to iodine deficiency. These include:

– Thiocyanates from cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage

– Phytoestrogens from soy products such as tofu, soy milk, and tempeh

– Smoking and environmental toxins such as chlorine, bromine, and fluoride

– Certain medications, such as lithium

– Perchlorate, an environmental toxin found in water supplies and cows’ milk

– Nitrates that are found in drinking water, leafy vegetables, root vegetables and processed meats.

If iodine intake is sufficient, goitrogens are unlikely to cause major issues. However, in iodine-deficient individuals, they can worsen hypothyroidism.

The risks of excess iodine

While iodine deficiency is harmful, excess iodine can also disrupt thyroid function. Proof of this is the Wolff-Chaikoff effect, which occurs when high iodine intake temporarily suppresses thyroid hormone production. This can potentially lead to hypothyroidism.

Current iodine recommendations

The recommended daily intake of iodine for adults is 150 µg. Pregnant and breastfeeding women need higher amounts (250 µg daily) to support fetal brain development.

Table 3. Recommended daily intake

RDI for iodine | Micrograms per day |

Younger children (1 to 8 years) | 90 |

Older children (9 to 13 years, boys and girls) | 120 |

Adolescents (14 to 18 years) | 150 |

Men | 150 |

Women | 150 |

Pregnany women | 220 |

Breastfeeding women | 270 |

Does iodine supplementation improve hypothyroidism?

Studies show mixed results. In mild to moderate iodine deficiency, increasing iodine intake can normalise thyroid function. However, in severe deficiency, excessive iodine intake can trigger thyroid dysfunction.

Conclusion

Balancing iodine intake is crucial. Undoubtedly, fortification programs have improved iodine status worldwide; however, some groups – especially pregnant women and children – remain at risk. Ensuring adequate iodine intake through diet, supplementation, or fortified foods can help prevent hypothyroidism and maintain optimal thyroid health.

To sum up, if you’re experiencing iodine deficiency symptoms or hypothyroidism, speak to All Naturopath today and live your best life! We can help you optimise your iodine levels and improve thyroid function.

Call All Naturopath today at 0402 926 675 for an appointment!

References

Review and Global Overview

Zimmermann MB, Boelaert K. Iodine deficiency and thyroid disorders. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(4):286-95.

Zimmermann MB, Jooste PL, Pandav CS. Iodine-deficiency disorders. Lancet. 2008;372(9645):1251-62.

Pearce EN, Andersson M, Zimmermann MB. Global iodine nutrition: Where do we stand in 2013? Thyroid. 2013;23(5):523-8.

Laurberg P, Cerqueira C, Ovesen L, et al. Iodine intake as a determinant of thyroid disorders in populations. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24(1):13-27.

National Surveys and Regulatory Sources

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Australian Health Survey: Biomedical Results for Nutrients, 2011-12.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ). Iodine in Food and Iodine Requirements. 2016.

Excess Iodine and Wolff–Chaikoff Effect

Wolff J, Chaikoff IL, Goldberg RC, Meier JR. Temporary inhibitory action of excess iodide on thyroid iodine synthesis. Endocrinology. 1949;45(5):504-13.

Koukkou EG, Roupas ND, Markou KB. Effect of excess iodine intake on human health. Minerva Med. 2017;108(2):136-46.

Sang Z, Chen W, Shen J, et al. Long-term exposure to excessive iodine in water and thyroid dysfunction in children. J Nutr. 2013;143(12):2038-43.

Fortification and Universal Salt Iodisation Outcomes

Hynes KL, Stanley J, Otahal P, et al. Iodine adequacy in Tasmania seven years after mandatory bread fortification. Med J Aust. 2018;208(3):126.

Shan Z, Chen L, Lian X, et al. Iodine status and thyroid disorders 16 years after universal salt iodisation in China. Thyroid. 2016;26(8):1125-30.

Laurberg P, Jørgensen T, Perrild H, et al. The DanThyr investigation on iodine intake and thyroid disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:219-28.

Krejbjerg A, Bjergved L, Pedersen IB, et al. Thyroid nodules in an 11-year DanThyr follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(12):4749-57.

Epidemiology of Thyroid Disorders

Allan Carlé P, Pedersen IB, Knudsen N, et al. Epidemiology of hypothyroidism subtypes in Denmark. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:21-8.

Pregnancy and Maternal Health

Blumenthal N, Byth K, Eastman CJ. Iodine intake and thyroid function in pregnant women before bread fortification. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:798963.

Moleti M, Lo Presti VP, Campolo MC, et al. Iodised-salt prophylaxis and risk of maternal thyroid failure in mild deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(7):2616-21.

Glinoer D, De Nayer P, Delange F, et al. Treating mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(1):258-69.

Child Cognition and Development

Zimmermann MB, Connolly K, Bozo M, et al. Iodine supplementation improves cognition in deficient schoolchildren. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(1):108-14